HOW DO BRAKES WORK? – Part 2: Disc Brakes and Drum Brakes

November 19, 2010 | in Defensive Driving TipsDisc Brakes

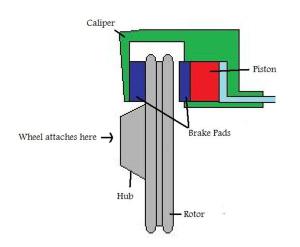

While there are several different kinds of disc brakes, the most common is the single-piston floating caliper. You’ll see what this means in a minute. This kind of brake has three main components: the brake pads, the caliper, and the rotor. (See figure 8.)

Figure 8: a disc brake

The brake pads are the rough friction surface that is pressed against the rotor to stop the wheel. The rotor is a round plate attached to the hub. The piston presses one brake pad against the wheel, while the caliper presses the other. The caliper is “floating” because it moves in a track that allows it to center itself over the rotor. As the brake fluid fills the cylinder, it pushes the piston to the left; however, it also pushes the caliper to the right. This allows both brake pads to press against the wheel simultaneously. Note that the brake pads don’t actually retract away from the rotor when the piston is released. Rather, they continue to press lightly against the rotor.

Remember that brakes produce a lot of heat. As a result, it’s important that the whole system be vented. Additionally, rotors are constructed with internal vents that dissipate heat. While once made of asbestos, brake pads today are made from various combinations of organic, metallic, and ceramic compounds.

Disc brakes are far more effective than their cousins, drum brakes. However, disc brakes are more expensive to manufacture and need to be made and aligned more precisely. If they come out of alignment, you’ll notice a dramatic shuddering when you brake. For this reason, many cars use disc brakes only on the front brakes. They then use drum brakes on the rear wheels. While drum brakes have more parts and are harder to service, they are cheaper and can easily accommodate an emergency brake mechanism.

Drum Brakes

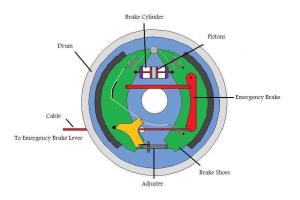

Like a disc brake, a drum brake uses friction to stop the car. The drum brake is also activated by pistons; in this case, the pistons cause two curved brake shoes to press against the inside of an iron drum, which is in turn located inside the wheel (See Figure 9).

Figure 9: Drum brake

Notice, however, that the system is slightly more complex than a disc brake. When the pistons activate the drum brake, the top edge of the brake shoe is the first part to contact the spinning drum. The spinning motion of the drum then pulls the brake shoes outward further, increasing the force with which the shoes press into the drum. As a result, the pistons on a drum brake can be smaller than those on a disc brake.

When the brake is released, the springs in the drum brake pull the shoes away from the drum again; otherwise, the wheels would be unable to spin due to the “pulling” action of the drum against the brake shoes. When driving in reverse gear, the opposite happens, i.e. the bottom part of the brake shoe is pulled against the drum.

As in a disc brake, the brake shoes will wear down over time. A drum brake compensates for this wear by means of an adjuster mechanism. This mechanism has two parts: a gear that is threaded onto a shaft, like a screw, and a lever (orange in the diagram) which is attached to the brake shoe.

When the car stops in reverse, the lever pulls against the adjuster as the drum pulls the bottom part of the shoe tight against the edge. If the gap between the brake shoe and the drum is too big, then the lever will pull the adjuster enough for it to slide forward a notch, lengthening the adjuster shaft. This pushes the bottoms of the brake shoes outwards, making the gap between shoe and drum smaller.

As you can see from the diagram above, it’s easy to add an emergency brake mechanism to a drum brake. Most emergency brakes are activated by a cable and lever system, like the one pictured above.

While disc brakes can incorporate emergency brakes, these systems are usually more complicated and expensive. In cars with only disc brakes, a second mechanism must be added to the brakes to accommodate the emergency brake function. This can take the form of a second, modified caliper system OR a kind of drum brake, built into the disc brake system.

The Combination Valve

It therefore makes sense to use a combination of disc and drum brakes in a car. Remember, however, that the disc brakes are always in contact with the rotor, while the drum brake shoes are pulled away from the drum walls. For this reason, the drum brakes need to move further in order to make contact with the wheel. In cars with both disc and drum brakes, the metering valve helps to compensate for this difference. The metering valve only allows pressure through to the disc brakes when a threshold pressure is reached. This means that power first goes to the drum brakes. However, the threshold is usually fairly low, so that the disc brakes engage only a little bit after the drum brakes.

The metering valve is one part of a combination valve, which contains several other valves as well.

The proportioning or equalizer valve accounts for the fact that there is a greater force on the front wheels when you stop. Bear in mind that wheels can only take so much force before they “lock up,” i.e. stop spinning. For this reason, jamming on the brakes too suddenly can cause you to go into a skid. In order to keep the back wheels from locking when more pressure is applied to the front brakes, the proportioning valve insures that more pressure is transmitted to the front brakes than the rear brakes.

The pressure differential valve is used to detect leaks in the braking system. This valve consists of a piston inside of a cylinder. Each side of this cylinder is then attached to one side or the other of the master cylinder. Pressure should thus be equal on both sides of the piston, keeping it in place. If the pressure changes, then the piston will move to one direction or the other. This activates a switch, which causes a brake warning light to turn on in the dashboard.

Read about Brake Basics in the first part of this series. Read about Power Brakes and Antilock Brakes in the third part of this series.

To read more on a broad range of subjects from “How To Change A Tire” to “How To Jumpstart Your Car”, visit DefensiveDriving.com’s Safe Driver Resources website!

Check out our defensive driving courses for more information about online defensive driving in Texas, California, Florida, and New Jersey.

← DefensiveDriving.com Offers Saturday Processing… | Florida Traffic School Course: Options Available →